A Mother Whale’s Pilgrimage to the Treasure Coast

Printed in Hobe Sound Magazine, November 2023

By Jill Griffin, Ph.D., Executive Director, Hobe Sound Nature Center

(in cooperation with the Nathaniel P. Reed Hobe Sound National Wildlife Refuge)

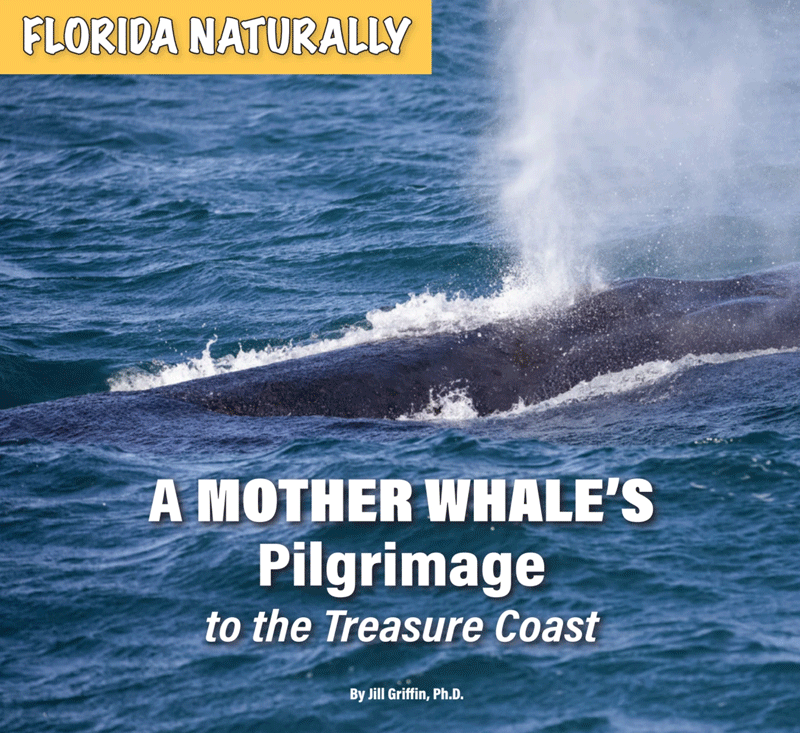

If you live in Hobe Sound or were visiting our beautiful town in January of this year, you may remember the media buzz surrounding a North Atlantic right whale and her calf lolling about in the warm tropical waters of the Treasure Coast. There’s nothing quite like being at the beach and spotting a 48-foot, 50-ton behemoth moving slowly through crystal blue waters, and this mama did not disappoint!

North Atlantic right whales are the most critically endangered whales in the world, with scientists estimating fewer than 350 remaining. They were given their name by early whalers, who considered them the “right” whales to hunt, given the convenience of their relatively slow speed and unusual buoyancy upon taking their last breath. These robust yet magical beasts narrowly escaped extinction in the late 1800s and are now careening toward the same fate of potentially disappearing from our planet forever. The natural world as we know it is changing. This means we must change with it, and the urgency to work together to mitigate the biggest threats to their existence - entanglements in fishing gear and vessel strikes – is palpable.

North Atlantic right whales are baleen whales, which is a group of cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) that lost their teeth over evolutionary time, only to be replaced with comb-like plates of strong yet flexible fibers, similar in composition to our fingernails. Right whales use their baleen like a sieve to filter tiny planktonic organisms from the water column as they cruise slowly with their mouths partially open. They gorge on plankton off the NE coast of the US and Canada during the warmest months of the year and then travel over 1,000 miles during the winter to give birth, fasting for many months to focus on their 2000-pound growing baby.

This incredible, first-time mama was known as “Pilgrim” by scientists, who studied her for years using photo-ID, in which individual right whales are identified by patterns of rough patches of white skin, called callosities, on their enormous heads. Pilgrim decided she was going to take the Sunshine State by storm and travel farther than most right whales, whose birthing grounds extend from Georgia to Cape Canaveral, Florida. As we all watched and gawked in awe, my colleagues from the University of Miami, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), and I wiped the pools of sweat from our brows, day after day, as we nervously anticipated her U-turn back to the waters of New England and Canada. There was a collective sigh of relief when she was spotted off the coast of North Carolina, traveling steadily northward. Though the public’s fascination with her was unmistakable, we know from experience, that proximity to humans comes with risks. Even those with the best of intentions could have changed the course of her life forever, which is why federal law mandates maintaining a distance of 500 yards from a North Atlantic right whale under the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972.

With less than 100 females remaining in the wild, the future of the North Atlantic right whale is bleak, at best. These giant whales only start reproducing at 10 years of age, have a 12-month gestation period, and invest heavily in their offspring. This means a single female is likely to produce only 5-6 calves in her lifetime, and that number is decreasing. It’s simple math, really. I, for one, have always loved math, but in this case, it’s a hard numerical pill to swallow. It’s nature’s checks and balances system, and the odds are not in the favor of the North Atlantic right whale.

This devoted, 11-year-old, first-time mother made her pilgrimage to the Treasure Coast and, in the most perfect yet unexpected way, left us all with a greater sense of admiration and respect for the ocean and the creatures that call the “big blue” home.